Adapted from Hagen, Karl. Navigating English Grammar. 2020. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A Smattering of Linguistics

Language is an extremely complex system consisting of many interrelated components. As a result, learning how to analyze language can be challenging because to understand one part you often need to know about something else. The bulk of this book concerns English sentence structure, which largely falls under the category of syntax, but there are other components to language, and to understand syntax, we will need to know a few basics about those other parts.

This chapter has two purposes: first, to give you an overview of the major structural components of language; second, to introduce some basic concepts from areas other than syntax that we will need to make sense of syntax itself.

We can think of language both in terms of a message and a medium by which that message is transmitted. These two aspects are partly independent of one another. For example, the same message can be conveyed through speech or through writing. Sound is one medium for transmitting language; writing is another. A third medium, although not one that occurs to most people immediately, is gesture, in other words, sign language. The message is only partly independent of the medium because while it is certainly possible to express the same message through different media, the medium has a tendency to shape the message by virtue of its peculiarities.

When we look at the content of the message, we find it consists of a variety of building blocks. Sounds (or letters) combine to make word parts, which combine to make words, which combine to make sentences, which combine to make a discourse. Indeed, language is often said to be a combinatorial system, where a small number of basic building blocks combine and recombine in different patterns. A small number of blocks can account for a very large variety indeed. DNA, another combinatorial system, uses only four basic blocks, and combinations of these four blocks give rise to all the biological diversity we see on earth today. With language, different combinations of a small number of sounds yield hundreds of thousands of words, and different combinations of those words yield an essentially infinite number of utterances.

The major components we are concerned with are the following:

- Phonology: The patterns of sounds in language.

- Morphology: Word formation.

- Syntax: The arrangement of words into larger structural units such as phrases and sentences.

- Semantics: Meaning. Semantics sometimes refers to meaning independent of any particular context, and is distinguished from pragmatics, or how meaning is affected by the context in which it is uttered. We, however, will not adopt that narrow interpretation, under the assumption that there really is no such thing as completely decontextualized meaning.

Phonology

Section contributors: Saul De Leon, Jodiann N. Samuels and an anonymous ENG 270 student.

Language varieties sound different from one another because the way language varieties have different inventories of speech sounds. The sounds that you hear—combined into words that make sense—is called phonology. There is no restraint to the number of distinct sounds that can be constructed by the human vocal apparatus. To that end, this unlimited variety is harnessed by human language into sound systems that are comprised of a few dozen language-specific categories known as phonemes (Szczegielniak). Phonology is the systemic study of sounds used in language, their internal structure, and their composition into syllables, words, and phrases. Sounds are made by pushing air from the lungs out through the mouth, sometimes by way of the nasal cavity (Kleinman). Think about this: All humans have a different way of pronouncing words that produce various sounds. Someone’s tongue movement, tenseness, and lip rounding (rounded or unrounded) are some examples in which sounds or even words are produced in different ways. Consider, for example, the sound of the consonant /ð/ represented by the written <th> in the English word <the>—this sound does not exist in French, but we can understand someone whose first language is French when they pronounce the same word with a /z/. Linguistics as a discipline is concerned with the regulation of sound patterns that speakers of any language produce that is geared toward communicating effectively. Phonology uses abstract models of human speech and language and thus explains the patterns that are used and how different rules interact with each other. Phonology is concerned more about the structure of sound instead of the sound itself; “Phonology focuses on the ‘function’ or ‘organization’ or patterning of the sound” (Aarts & McMahon pg. 360)

In this chapter, you will learn that all languages have an inventory of sounds (essentially, they have different numbers of phonemes) and rules for those sounds. By way of illustration, in English, the phoneme /ŋ/,the last sound in the word ding, will never appear at the beginning of a word.

Throughout this section, we will use the conventional / / slashes to indicate International Phonetic Alphabet representations of phonemes (the sounds of language) and < > brackets to indicate orthography (the way things are spelled in the standardized English writing system)

Phonemes

Buzz. Pop. Hiss. Say the following out loud: Vvvv. It has a “buzz” sound that ffff does not have, right? Keep in mind that the “buzz” sound is caused by the vibration of your vocal folds. When you are speaking to someone, you automatically ignore nonlinguistic differences in speech (i.e., someone’s pitch level, rate of speed, coughs) (Szczegielniak). Speech sounds are produced by moving air from the lungs through your larynx, the vocal cords that open to allow breathing—the noise made by the larynx is changed by the tongue, lips, and gums to generate speech. Most importantly, however, sounds are different from letters that are in a word. For example, a world like English has seven letters (E-n-g-l-i-s-h), six sounds (/ɪŋɡlɪʃ/), and two syllables. We often tend to think of English as a written language, but when studying phonology, it’s important not to conflate sounds and letters. This is more often true in English than in many other languages that use alphabets for their scripts; not only are the correspondences between sounds and letters not always one-to-one, sounds are often pronounced in many ways by different people.

Phonemes are a vital part of speech because they are what dictates how a sound of letter or word is distinguished which differentiates the meaning of words. Sometimes a letter is more than one phoneme (<x> is often pronounced /ks/) and sometimes two or three letters are used to represent a single sound (like <sh> for the phoneme /ʃ/ ).

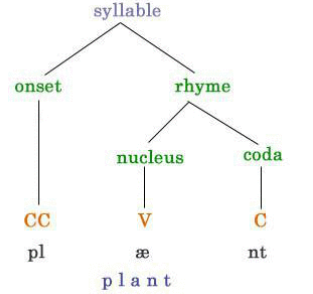

The sounds of a word can be broken down into phonemes, the smallest units of sound that distinguish meaning. These basic sounds can be arranged into syllables and a metrical phonological tree can be used to simplify breaking up a syllable (i.e. Diagram A) (AAL Alumnae, Gussenhoven & Haike).

Diagram A

Example: The word plant.

Image source: AAL Alumnae. All About Linguistics, all-about-linguistics.group.shef.ac.uk/branches-of-linguistics/phonology/.

A syllable consists of an initial sound or onset and followed by another sound called a rhyme. A rhyme is further split into a nucleus which are the vowel sounds and the coda which are the consonants that come after the nucleus. The onset is simply the consonants before the rhyme. These aspects are all brought together to identify the differences of languages due to each language’s unique phonemes and syllable structures. (AAL Alumnae, n.d.).

Generally, decoding the entirety of a language’s structural system is ambitious as linguists face the challenge of the evolution of language and simply that some are dying out too quickly. So, this has forced linguists to adapt to a goal to identify common factors across languages. They rely on components such as cognitive factors (characteristics that influence an individual’s learning capabilities), phonetic factors (the speech production system), and social factors (the human experience) (Gussenhoven & Haike, 2017, p. 5).

This is an important segue into the distinction between phonology and phonetics. Phonetics involves the study of the way sound is produced by certain parts of the body. The synchronous use of body parts such as but not limited to the mouth, teeth, tongue, voice box or larynx, and pharynx are involved with making speech sounds and what sounds exist in a language. In relation, phonology is the arrangement of these speech sounds and how they are treated. Furthermore, it can even analyze the distinction between distinctive accents or challenges native speakers may face attempting to acquire another language when facing phonemes that are not a part of their language (FSI, n.d.; Gussenhoven & Haike, 2017, p. 17).

There are about 200 phonemes across all known languages; however, there are about forty-four in the English language and the forty-four phonemes are represented by the twenty-six letters of the alphabet (individually and in combination). The forty-four English sounds are thus divided into two distinct categories: consonants and vowels. A consonant gives off a basic speech sound in which the airflow is cut off or restrained in some way—when a sound is produced. On the other hand, if the airflow is unhindered when a sound is made, the speaker is producing a vowel. (DSF Literary Resources). Even with diphthongs, or sequences of two vowels, your tongue changes when you say a different vowel.

Phonology and Phonetics

Phonology involved a fair degree of formal analysis and abstract theorizing. The primitive objective of phonology is to understand the system of rules that a speaker uses in considering the sound of the language (Hayes). Thus—to be crystal clear—phonology is more theoretical, concerning not directly with the physical nature of speech sounds, but with the unconscious rules for sound patterning that are found in the mind and brain of a person who speaks a particular language. Think of someone who simply studies the sound pattern of a language—a phonologist—and consider how sounds flow in the air from person-to-person and how sounds vary with context (often in a compounded way). On this score, phonology is like other elements of grammar, (for instance, morphology, and syntax), and there are distinct rules that characterize how sound patterning reflects information that arises within these components (Hayes). On the contrary, phonetics is the study of speech sounds: how sounds are produced, how they are perceived, and what their physical properties are. There are three branches of phonetics: 1). Acoustic: the physics of sound 2). Auditory: how the ear processes sound and 3). Articulatory: how we produce speech sounds. There is, indeed, a phonetic system that linguistics use to record speech sounds. Significantly for present purposes, linguists use the phonetic alphabet called the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which uses a different symbol to represent each phoneme. Many of the (IPA) letters are like the English alphabet and it is also important to note that linguists don’t all necessarily follow this accepted international standard (California State University, Northridge).

Minimal Pairs and Allophones

Understanding how to pronounce and to make a clear distinction of letters is essential to the structure of a language sound system. In English and other languages, there are many words that sound similar to one another, but differ in a single sound, like ‘pit’ and ‘bit’, or like ‘leap’ and ‘leave’. Linguists call these minimal pairs. “Minimal pairs are word that differs in one phoneme” (McArthur Oxford Reference). Even though they end identically both words are completely unrelated to each other in meaning. Minimal pairs are useful for linguists because they provide comprehension into how sounds and meanings coexist in language. They tell us which sounds (phones) are distinct phonemes, and which are allophones of the same phoneme.

Allophones are a related concept, in which a single phoneme can be produced differently in different circumstances. For example, the phoneme /k/ in the word ‘kite’ is aspirated, meaning it’s accompanied by a puff of air. But in the word ‘sky’ there is no puff of air along with the /k/ sound. We still think of these as the same sound, and they don’t occur in the same positions, which makes them allophones of a single phoneme.

Allophones are determined by their position in the word (potential, impartial, essential, etc.) or by its phonetic environment. Speakers often have issues with hearing the phonetic differences between allophones of the same phoneme because these differences do not serve to distinguish one word from another. In English, the t sounds in the words “hit,” “tip,” and “little” are all allophones (Britannica)—they are all the same sound, though they are different phonetically in terms of voice and articulation.

Phoneme and Phonemic Awareness

By the age of five, without developmental restrictions, a child would have learned how to speak a language. Also, at this developmental stage they would have innately acquired their language structure through their environment or experience (Gussenhoven & Haike, 2017, p. 1, 94). Phonological awareness is the capacity of a child to realize words are comprised of various sound units. This allows the child to understand that words begin with basic sound units such as /b/, /a/, /t/ in the word ‘bat’ are a part of a more complex, larger sound “chunks” or syllables (K12 Reader, 2019).

A child that has strong phonological awareness should be able to dissect a syllable, blend phonemes, and recognize related forms (“cat” from the larger word catalog). Additionally, phonemic awareness is a subset of phonological awareness that gauges the child’s ability to identify the differences in a string of words such as in an alliteration (i.e. tongue twisters: She sells seashells by the seashore), a rhyme, and the ability to blend or fragment phonemes (K12 Reader, 2019).

Syntactic Structure

Both syntax and phonology are components of language; however, they are not often linked as they cover two different disciplines. What they both address at their core is the structure of the language. Danish linguist Louis Trolle Hjelmslev developed the theory that rather than exploring the separate fields of linguistics independently they should be viewed synchronously. His model of ‘analogie du principe structurel’ would influence other works to create parallels to compare syllable structure of onsets and rhymes to that of the NP/VP (noun phrase and verb phrase) split in clausal organization.

Phonology and syntax represent layers of a combination of sounds that are quintessential to a language. The ways in which phonology and syntax relate are manifold. Firstly, syntax is how the words are arranged in a sentence (the word order), and the rules that indicate how words can be combined to form sentences in a language, and on the other hand, phonology is the sounds that are heard when someone speaks, or read a speech out loud and both syntax and phonology interface with each other because both are key elements of the structure of language at different levels.

Citations:

AAL Alumnae. “Why Study Phonology”. University of Sheffield. 2012a. https://sites.google.com/a/sheffield.ac.uk/aal2013/branches/phonology/why-study-phonology Accessed 09 September 2020.

AAL Alumnae. “Language Acquisition”. University of Sheffield. 2012b. https://sites.google.com/a/sheffield.ac.uk/aal2013/branches/language-acquisition Accessed 09 September 2020.

Anderson, Catherine. “4.2 Allophones and Predictable Variation.” Essentials of Linguistics, McMaster University, 15 Mar. 2018, https://essentialsoflinguistics.pressbooks.com/chapter/4-3-allophones-and-predictable-variation Accessed: 21 September 2020.

Bromberger, Sylvain, and Morris Halle. “Why Phonology Is Different.” Linguistic Inquiry, vol. 20, no. 1, 1989, pp. 51–70. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4178613 Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

Collier, Katie, et al. “Language Evolution: Syntax before Phonology?” Proceedings: Biological Sciences, vol. 281, no. 1788, 2014, pp. 1–7. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43600561. Accessed 7 Sept. 2020.

Coxhead, P. “Natural Language Processing & Applications Phones and Phonemes.” University of Birmingham (UK), 2006, www.cs.bham.ac.uk/~pxc/nlp/NLPA-Phon1.pdf

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Allophone.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Feb. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/allophone .

FIS. “Phonetics and Phonology.” Language Differences – Phonetics and Phonology. Frankfurt International School. https://esl.fis.edu/grammar/langdiff/phono.htm Accessed 09 September 2020.

Goswami, Usha. “Phonological Representation.” SpringerLink, Springer, Boston, MA. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6 Accessed: 21 September 2020.

Gussenhoven, Carlos, and Haike, Jacobs. Understanding phonology. London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017. https://salahlibrary.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/understanding-phonology-4th-ed.pdf Accessed: 05 September 2020.

Hayes, Bruce. Introductory Phonology. John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

Hellmuth, Sam, and Ian Cushing. “Grammar and Phonology.” Oxford Handbooks Online, 14 Nov. 2019, www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198755104.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780198755104-e-2

Honeybone, Patrick, and Bermudez-Otero, Ricardo. “Phonology and Syntax: A Shifting Relationship.” Lingua, 22 Oct. 2004, pp. 543-561. www.lel.ed.ac.uk/homes/patrick/lingua.pdf Accessed 21 September 2020.

K12 Reader. “Phonemic Awareness vs. Phonological Awareness Explained.” Phonemic Awareness vs Phonological Awareness. K12 Reader Reading Instruction Resources, 29 Mar. 2019. www.k12reader.com/phonemic-awareness-vs-phonological-awareness/ Accessed 21 September 2020.

Kirchner, Robert. “Chapter 1 – Phonetics and Phonology: Understanding the Sounds of Speech.” University of Alberta, https://sites.ualberta.ca/~kirchner/Kirchner_on_Phonology.pdf.

American Speech-Language Hearing Association. “Language in Brief.” American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Spoken-Language-Disorders/Language-In–Brief/

Kleinman, Scott. 2006. “Phonetics and Phonology.” California State University, Northridge, www.csun.edu/~sk36711/WWW/engl400/phonol.pdf

Szczegielniak, Adam. “Phonology: The Sound Patterns of Language.” Harvard University, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/adam/files/phonology.ppt.pdf

Aarts, Bas, and April McMahon. The Handbook of English Linguistics. 1. Aufl. Williston: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. Print.

De Lacy, Paul V. The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology. Cambridge University Press, 2007. Print.

McArthur, Tom, Jacqueline Lam-McArthur, and Lise Fontaine. Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2018. Print.

Philipp Strazny. Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 1st ed. Chicago: Taylor and Francis, 2013. Web.

Speech vs. Writing

Section contributors: Terrell McLean and two anonymous ENG 270 students.

We first learn to speak when we are children, and we do this for at least five years of our lives before we learn to write. Once we learn to do both of these, we think we have mastered the ways of communicating, forgetting that: 1) these two are not the only ways we communicate, and 2) the line, in some cases, is blurred concerning the difference between speech and writing.

Linguists have given more attention to oral communication, giving it more authority and validation, which suggests that written communication is secondary—we learn to speak before we learn to write. However, both speech and writing are forms of language use and deserve equal amounts of recognition.

Differences between Speech and Writing

Let’s take a deeper look at writing and speech. What are some of the distinctions between them? Writing is edited; we can more easily delete or rewrite something over again to make sure how we want to come across is shown in our writing. We can prewrite and brainstorm, which is an effective way of writing (Sadiku 31). This is something we cannot do as we speak. Another reason writing is different from speech because writing is not something everyone can do. Literacy, or the ability to read and write, is not universal, though it is more common today than in previous eras. In some communities today, there are individuals who do not have the skill of writing amongst their neighbors who can. Among the 7000+ languages that exist in the world, more than 3,000 do not have a written language (“How Many Languages in the World Are Unwritten?”) and only 23 languages are spoken by half the population of the world (“Languages in the World”). Written language has historically been seen as a mark of prestige.

The majority of people learn how to speak by the time they are two years old. As we communicate through speech, we have the option of speaking informally or formally. Someone who only speaks formally might find that others say, “You talk like a book” (Bright 1); the book being a textbook or some form of an academic book. However, we all lean towards informal speech when we are surrounded by people we are comfortable with or when we want to be casual.

A greater range of expression is available when using speech because you can use the tone of your voice to express how you feel when you talk about a certain topic. However, the way you use your voice can have many meanings. For example, shouting can mean that you are angry, excited, or surprised. Sometimes you might have to use an extra sentence to connect your tone of voice to how you feel. With writing, a lot of this paralinguistic content (pitch contours, tone of voice) is not available to the reader, but there are strategies writers use like writing in all capital letters or using various forms of punctuation (not a feature available in speech) to compensate.

Finally, a distinction of writing is its durability. Composed messages are passed on through time as well as through space. With writing, we can keep in touch with somebody nearby or on the opposite side of the world (although advances in communication technology have made this true of speech as well).

Similarities between Speech and Writing

In the sections above, we’ve examined differences between speech and writing, but these two forms of language and communication do have similarities as well. Let’s take the example of formal and informal writing and speech. As mentioned before, we can talk informally—talking casually in conversations, or when you’re talking to someone close to you—and this can be done by using slang, short words, and a casual tone of voice. While writing is often thought of as formal by nature, informal writing can also be acceptable in a number of contexts, like freewriting. This is one of the ways we can write informally. In this form of writing, we can write down all the things that come to mind, however we want to write it; it doesn’t matter the quality of the writing or how we produce sentence structure (Elbow 290). Informal writing can also be found in much of what is called Computer-Mediated Communication, or CMC. One example is personal blogs, which are often different from more formal news articles. Blog posts have more flexibility to be informal because most people write with a conversational tone to appeal to their audience.

Writing has often been differentiated from speech by the nature of its participation. According to classical views, when we write, we write by ourselves; writing is done independently. Speech on the other hand is understood to take more than one person because we need at least two people to hold a conversation; therefore, speech is dependent on another person. However, technology has blurred the lines here as well. For example, take the CMC mode of the internet forum (Elbow 291). This media is a form of constant writing where we can continuously respond to people without interruption. This has been set in place since the 70s and one that is popular today that has a collection of forums pertaining to different topics is Reddit. YouTube is also a great example of this because while we watch a video on a particular topic, we can then respond in the comment section immediately and give our own opinions. This conversation can continue with the person in the video and other people that may agree or disagree with you.

Prescriptivism and Descriptivism in Writing

Language is presented in many forms but one of the most traditional and lasting of them all is that of written works. These include folktales that pass along valuably moral messages from one generation to the next, stories detailing societies of old, and many genres of fiction and nonfiction. While oral histories were transmitted (and still are in some cultures), the more common situation today is that a society’s output is represented in written work. Written works take the values, thoughts and viewpoints of a time period and turn them into a time capsule.

Even with that, there are those on the one hand who wish to standardize and those on the other hand who wish for a certain grammatical freedom mostly present in speech. Those who wish for written language to be more uniform are known as prescriptivists. Those who agitate for more freedom and a written language which reflects the freedoms of speech could be called descriptivists. As noted in 63 Grammar Rules for Writers by Robert Brewer, “On one hand, grammar rules are necessary for greater understanding and more effective communication.” (Brewer, Writer’s Digest). Prescriptivists would agree with this, arguing that both reading and writing become easier with clear guidelines of what certain things should look like. However, another thing noted by Brewer is that “On the other hand, there are just so many rules (and so many exceptions to the rules). It can be overwhelming.” (Brewer, Writer’s Digest). While strict prescriptivism has its advantages, it can be overwhelming to those who want to write freely without confinement to rules. Also, it can limit the artistic expression one may possess. So even though both seek make writing more accessible, the ways that they promote it are different. One wants to make writing more uniform and homogenized, while the other seeks freedom and diversity in the words used.

Speech, Writing, and Syntax

Syntax is the way words are arranged to form sentences, and is a part of all linguistic communication, regardless of whether it is written or spoken. However, there can be differences in the syntax of speech vs. writing. In a study with 45 students, Gibson found that speech “has fewer words per sentence, fewer syllables per word, a higher degree of interest, and less diversity of vocabulary” (O’Donnell, 102). In another study that Drieman did in Holland, he found that speech, compared to writing, has “longer texts, shorter words, more words of one syllable, fewer attributive adjectives, and a less varied vocabulary” (O’Donnell, 102).

While many think of prescriptive rules applying primarily to written grammar, speech is seen as more lenient, allowing for fluidity nor replicated in written works. However, it comes with own fair share of complexities and rules that need to be managed, one of them being syntax. Syntax is the structuring of words and their overall arrangement in relation to each other. Even though grammar isn’t as strict when it comes to writing a lot of the same principles follow, words need to flow in a cohesive manner that is understandable to others. Even with slang and regional dialect coming into play, syntax creates a cohesive use of language during a conversation. Even in complex usages of language such as code-switching (the use of multiple language varieties in a single discourse event) the necessity for clear structure and communication lies under all of that. In Code Switching and Grammatical Theory the idea is presented that even with code switching in the middle of a sentence, there is a grammatical structure: “In individual cases, intra-sentential code switching is not distributed randomly in the sentence, but rather it occurs at specific points” (Muysken, 155).

Conclusion

Even though both speech and writing require the use of syntax to remain cohesive, the differences between writing and speech are clear and abundant; as Casey Cline writes, “Speech is generally more spontaneous than writing and more likely to stray from the subject under discussion.” (Cline, Verblio). Written works, on the other hand, are usually seen as something that must stay grammatically correct, thus not being able to always mimic the freedom of speech. As put in Grammar for Writing? “… Grammar is frequently presented as a remediation tool, a language corrective.” (Debra Myhill, 4). However, formal speech and informal writing have existed for a long time, and new communications technologies have increasingly challenged the distinctions between speech and writing.

References

Bailey, Trevor. Jones, Susan. Myhill Debra A. “Grammar for Writing? An investigation of the effects of contextualized grammar teaching on students’ writing”. University of Exeter, 2012.

Brewer, Robert L. “63 Grammar Rules for Writers”. Writer’s Digest, 2020, pp. 4. https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/grammar-rules-for-writers/

Bright, William. “What’s the Difference Between Speech and Writing.” Linguistic Society of America. https://www.linguisticsociety.org/resource/whats-difference-between-speech-and-writing. Accessed 22 September 2020.

Chafe, Wallace, and Deborah Tannen. “The Relation between Written and Spoken Language.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 16, 1987, pp. 383–407. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2155877. Accessed 22 September 2020.

Cline, Casey. “Do You Write the Way You Speak? Here’s Why Most Good Writer’s Don’t”. Verblio, 2017. https://www.verblio.com/blog/write-the-way-you-speak/.

Elbow, Peter. “The Shifting Relationships between Speech and Writing.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 36, no. 3, 1985, pp. 283–303. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/357972. Accessed 22 September 2020.

“How Many Languages Are There in the World?” Ethnologue: Languages of the World. https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages

“How Many Languages in the World Are Unwritten?” Ethnologue: Languages of the World. https://www.ethnologue.com/enterprise-faq/how-many-languages-world-are-unwritten-0. Accessed 6 October 2020.

Muysken, Pieter. “Code-Switching and Grammatical Theory”. One Speaker, Two Languages: Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Code-Switching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Text, 1995 pp.155.

O’Donnell, Roy C. “Syntactic Differences Between Speech and Writing.” American Speech, vol. 29, no. ½, 1974, pp. 102–110. JSTOR, https://www-jstor-org.york.ezproxy.cuny.edu/stable/3087922. Accessed 22 September 2020.

Morphology

Contributors: Paul Junior Prudent and an anonymous ENG 270 student

Definition

Morphology is a branch of linguistics that deals with the structure and form of the words in a language (Hamawand 2). In grammar, morphology differs from syntax, though both are concerned with structure. Syntax is the field that studies the structure of sentences, which are composed of words, while morphology is the field that studies the structure of the words themselves (Julien 8).

Morphemes

In language, some words are made up of one indivisible part, but many other words are made up of more than one component, and these components are called morphemes. A morpheme is a minimal unit of lexical meaning (Hamawand 3). So, while some words can consist of one morpheme and thus be minimal units of meaning in and of themselves, many words consist of more than one morpheme. For example, the word “peace” has one morpheme and cannot be broken down into smaller units of meaning. Peaceful has two morphemes, peace the state of harmony that exists during the absence of war, plus -ful, a suffix, meaning full of something. Peacefully has three morphemes: peace + –ful + –ly, with the final morpheme –ly indicating ‘in the manner of’. So really, peacefully contains three units of meaning that, when combined, give us the meaning of the word as a whole. Words can have a lot more than three morphemes, however (Kurdi 90).

Comparative Morphology

In some languages, there are only simple words and compounds, and therefore very little morphology—most of the grammatical complexity is syntactic in these languages. Languages like these are referred to as having an isolating morphology. On the other end of the scale, languages that combine many morphemes to produce words are referred to as polysynthetic. Polysynthetic essentially means that the language is characterized by complex words consisting of several morphemes, in which a single word may function as a whole sentence. Modern English is closer to the isolating end of the spectrum, while still having a productive morphology. Languages like this are known as analytic languages, in which sentences are constructed by following an order of words.

Types of morphemes

Morphemes can be further divided into several types: free and bound. Free morphemes are the morphemes that can be used by themselves. They’re not dependent on any other morpheme to complete their meaning. Open-class content words (generally speaking, nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) such as girl, fish, tree, and love are all considered free morphemes. As are closed-class function words (prepositions, determiners, conjunctions, etc.) such as the, and, for, or it (Hamawand 5). Bound morphemes are another class of morphemes that cannot be used by themselves and are dependent on other morphemes.

Bound morphemes are further divided into two categories: affixes and bound roots (Kurdi 93). Bound roots are roots that could not be used by themselves. For example, the morpheme -ceive in receive, conceive, and deceive cannot stand on its own (Aarts et al. 398). Affixes occur in English primarily as prefixes and suffixes. Prefixes are morphemes that can be added to the front of a word such as pre- in preoccupation, re- in redo, dis- in disapprove or un– in unemployment. Morphemes that can be added to the end of a word (a suffix) such as –an, -ize, -al,or -ly. In other languages, there are morphemes that can be added to the middle of a word called infixes, and morphemes that can be added to both sides of a word called circumfixes. English also has limited infixation, usually in casual speech and involving taboo language: consider abso-goddamn-lutely or un-fucking-believable. In terms of function, affixes can be divided into two categories of their own: derivational affixes and inflectional affixes (Hamawand 10).

Types of affixes

Derivational affixes are affixes that when added to a word create a new word with a new meaning. They’re called derivational precisely because a new word is derived when they’re added to the original word, and many times these newly created words belong to a new grammatical category. Some affixes turn nouns into adjectives like beauty to beautiful, some change verbs into nouns like sing to singer, and some change adjectives to adverbs, like precise to precisely. Still others turn nouns to verbs, adjectives to nouns, and verbs to adjectives. Other affixes do not change the grammatical category of the word they’re added to. Adding -dom to king yields kingdom, which is still a noun, and adding re- to do yields redo, still a verb. We use derivational affixes constantly and they’re a very important part of English because they help us to form the majority of words that exist in our language (Aarts et al. 527-529).

In English, the other type of affix, inflectional affixes are suffixes that when added to the end of the word don’t change its meaning radically. Instead, they change things like the person, tense, and number of a word. And in English, there are a total of eight inflectional affixes:

- The third person singular –s as in Anakin kills younglings,

- the past tense -ed as in Ron kissed Hermione,

- the progressive –ing as in Han is falling into the sarlacc pit,

- the past participle –en in the Emperor has fallen and cannot get up,

- the plural –s in vampires make the worst boyfriends,

- the possessive -‘s in that’s Luke’s hand isn’t it,

- the comparative –er in the car is cooler than Kirk, and

- the superlative –est in that’s the sweetest thing I’ve ever seen.

Compared to other languages English has very few inflectional affixes. (Aarts et al. 510).

The Relationship between Morphology and Syntax

Morphology and Syntax are two different but related fields in English grammar. Syntax studies the structure of sentences, while morphology studies the formation of words. However, both domains must interact with each other at a certain level. On one level, the morpheme should fit a syntactic representation or a syntactic structure. And in another level, the morpheme can have its syntactic representation. That notion is called “the syntactic approach to morphology” by Marit Julien (8).

References

- Aarts, Bas, and April McMahon. “The Handbook of English Linguistics.” The Handbook of English Linguistics, 1. Aufl., Wiley-Blackwell, 2008.

- Hamawand, Zeki. Morphology in English Word Formation in Cognitive Grammar

Continuum, 2011.

- Julien, Marit. Syntactic Heads and Word Formation A Study of Verbal Inflection. Oxford

University Press, USA, 2002.

- Kurdi, Mohamed Zakaria. “Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics 1: Speech, Morphology and Syntax.” Natural Language Processing and Computational Linguistics 1, John Wiley & Sons (US), 2016.

Lexical Semantics

[To be added]